The New York Times ran a story yesterday that includes the results from an interesting study about people who buy home exercise equipment:

People with a home exercise machine were 73% more likely to start exercising. But by the end of the year, they were also 12 percent more likely to have quit than people in the study who did not have home equipment.

In October, the journal Annals of Behavioral Medicine reported on a study of 205 sedentary adults who were encouraged to begin an exercise program. At 6 months, about half had done so, but by 12 months, about a third of those people had stopped.

So if you spring for a piece of home exercise equipment, you’re actually less likely to stick with a new exercise program than if you joined a gym, say, or just started gadget-free walks or runs around the neighborhood.

Sounds a little counter-intuitive, right? A home gym is convenient, private, easy to use. No schlepping to and from a crowded gym with inconvenient hours, no gawking guys in string tank tops who don’t wipe the sweat off the equipment, no lines for your favorite glute-busting machine, no scuzzy shower room. Just your own really cool, convenient, effective, state-of-the-art….laundry-drying rack.

When I was a lad, I carried papers for the Valley News for something like eight months to save up the 400 bucks so I could spring for my half of a Soloflex home gym (my Dad agreed to pay the other half, bless him). Young bucks won’t remember the Soloflex, but before the Bowflex came along and crushed it, Soloflex was the cool, upcale home-gym of choice. (eds. note: the founder/CEO of Soloflex comments on the Bowflex/Soloflex throwdown in the comments section below. Worth a look.–A)

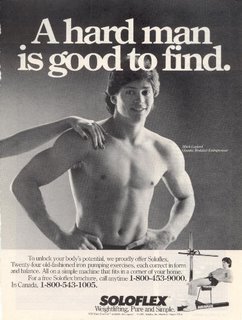

They even used a smirking Frank Zane in their ads, and ran them in TIME and NEWSWEEK. I remember they billed Zane as a “mathematician/entrepreneur” rather than the “Three-time Mr. Olympia” that he was; the better to imply that you too could build a world-champion physique on a rubber-band stretching device (I’m disappointed I can’t find the Zane ads, but the one above features Olympic gymnast Mitch Gaylord, and that’s almost as bad).

Anyway, as I schlepped that sack of newspapers through the sleet and snow of Hanover, New Hampshire every afternoon, dreaming of pumped-up muscles and feeling like a kid out of Dickens, I remember a certain feeling of dread: maybe building a physique that would inspire ladies to tweak my ear, as they tweaked Zane’s in the ads, was going to be a little bit tougher than I thought. Maybe I’d get discouraged and the Soloflex would lie around in the house, a high-priced token of my failure.

That never happened; I actually attacked that thing with a vengeance. But I think eight months of paper-schlepping will do that to a kid: whether it’s a Soloflex or a Camero, you love the hell out of that first big thing you pay for yourself. Would that were true into adulthood.

Now I’m not going to get all In-my-day, I-Had-To-Deliver-Newspapers-For-Eight- Months-to-Save-Up-for-a-Piece-of-Exercise-Equipment on you. But I will say this: every trainer has a story of at least one client who pays for sessions and for whatever reason, never shows up. There’s a twisted belief out there that you can buy your way out of doing the real work it takes to get in shape. That if you buy personal training sessions, or a gadget on TV, or the latest cross-trainers, that the work magically does itself.

Most trainers’ clients, at some point, will say that that they wish they could pay someone to work out for them. It’s only a half-joke. If that.

I think part of the reason that fitness is such big business is that it just ain’t that hard to convince someone that if you throw money at a problem, you’ve solved it. We throw money down the fitness wishing well because we don’t want to jump in there ourselves.

But in fact, let me remind you again, that you don’t have to spend one thin dime to get fit. Not one thin dime. Whether we stick to an exercise program depends not so much on how much we spend, as the article says. It’s something much more intangible:

What matters more is “self-efficacy” — a deep-seated belief that we really do have the power to achieve our goals. In the Annals study, those who scored high on psychological measures of self-efficacy were nearly three times as likely to be exercising after a year as those with lower self-efficacy scores, whether or not they owned an exercise machine.

Leave a Reply